Chief Brian Dean

Strategic planning in the fire service still appears, in many regards, in its infancy. Taking the concepts from the global and United States private sectors, the idea of strategic planning has slowly trickled down to the specific governmental units, divisions, or departments of municipalities and counties, as well as fire districts and industrial fire service entities. While there seems to be no firm research on why public safety entities shy away from strategic planning, one theory may be, does the private sector model of shareholder-centric strategic planning work for the public sector? One might also question if the causal effect is based more on a confusion of which best practices to apply to fire and emergency service departments. Finally, one might wonder if any emerging trends exist to clarify the applicability of a typical strategic planning model to the fire service.

The fire service has a long traditional history that tends to celebrate the best of what has happened. The fact that many organizations continue to operate in the status-quo, grounded in those traditions, makes one wonder how progression in a proactive manner could ever happen. It is that reactive nature that has stagnated many organizations. The lack of strategy, vision, and a guiding coalition for change keeps many departments defaulting to the understanding that “we have always done it that way.” When strategic planning was first introduced for the private sector, it delivered a better focus for industry and business in thinking about its future. Much like the private sector of over 50 years ago, the fire service and the public sector of today face challenges not necessarily from competition but rather, from the economic and political external environment that provide the funding of public safety.

Strategic planning has many benefits, but the greatest is its ability to design a roadmap for future success. Would you ever consider taking a journey without a plan? Strategic planning provides the benefit of knowing what direction your agency will travel in the next three to five years. Much like a compass provides directional orientation, a strategic plan orients the department on where to take things in the future, toward an intended outcome. Additionally, if the plan is designed as a living instrument, another benefit exists…the ability to recalculate. In this day and age, most are equipped with devices that provide the navigational guidance to find our way around successfully. However, take one wrong turn, as many are apt to do, and the devices must recalculate. A strategic plan is no different if implementation is the focus and if the understanding exists that one cannot foresee what may happen in the future. A strategic plan is just that, a plan. It is not a list of tasks with no meaning but rather, a flexible navigational tool that provides direction toward intended outcomes and change.

The general perspective of Dr. Drucker’s futurity of present decisions has applicability to any entity in that if one considers what it needs to do from today, the future vision can become reality. Fire service organizations need to determine where they should be in relation to community expectations, acknowledgement of their concerns and make those appropriate process decisions to overcome the true strategic challenges. They must, however, engage not only in the planning process, but the implementation of the identified objectives to overcome those illuminated challenges. The accreditation model, as prescribed by the Commission on Fire Accreditation International (CFAI), understands the noted futurity and guides the fire service towards a process to embrace change and continuous improvement. Focusing on true strategic challenges, those things that are not simple (tactical), create the most change within an organization and produces quality outcomes through proper implementation efforts.

True strategic challenges are broad and are genuinely of a type that the department can impact with specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound change. In reality, those strategic challenges and hopefully, initiatives, are few and dependent on the intensity of the organization. So, what is meant by that? There are some departments that have a perfect symbiosis internally and with its governance that things transition smoothly. On the norm in public safety, symbiosis exists but it may be hampered by the justification component. That is where a comprehensively constructed strategic plan is used to justify the request for funding in the budgeting process. Other organizations may not have any level of said symbiosis or even the resources to take on a set of initiatives over the three to five-year duration of a plan. In short, fire departments need to know how much to bite off in the development of goals, objectives, and tasking to achieve the desired outcomes. Taking on too much can result in overload that hampers creativity and hinders overall strategic success.

When questioning the applicability of a business model to the public sector, research shows that the model is appropriate if applied with strategy in mind. Strategic planning is not about acquiring stuff. Rather, it is about building systems and processes that pursue outcomes, that can also be institutionalized for continuous improvement. This provides a long-term return on investment if the plan’s execution produces the outcomes envisioned. It also provides the opportunity to re-calculate if the outcomes fall short.

Research exists on the applicability that follows a basic schematic that ensures there is understood and considered feedback from community stakeholders. Often times, an agency is unsure of who constitutes as a community stakeholder. Examples of such could include members of the business community, residential association representatives, administrators from local hospitals or school districts, mutual or automatic aid partners, members of governance, or even direct recipients of the agency’s emergency services. Anyone outside of the agency that has a stake or is a partner can provide the needed feedback. This is the customer base of the fire service. Without it, how can a department truly understand what the end-user thinks? Your community stakeholders provide insight into what the environment truly is once you leave the apparatus bay. Understanding what your customer expects and about what they are concerned can help you further identify the gaps and challenges your department is facing. If you don’t ask them, you will never know!

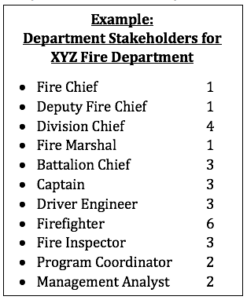

From an internal participatory perspective, agency stakeholder representation should be from different levels and points within the organization. Not only does this create a buy-in component when implementation is in play, but also gets different perspectives, be they generational, cultural, or knowledge-based as the strategic plan is formulated. Just like a corporate strategic plan must include organizational members on all levels, fire departments must ensure that all levels and demographics are represented in the plan deliberation. A plan that is created by the leadership team alone is doomed to fail.

From an internal participatory perspective, agency stakeholder representation should be from different levels and points within the organization. Not only does this create a buy-in component when implementation is in play, but also gets different perspectives, be they generational, cultural, or knowledge-based as the strategic plan is formulated. Just like a corporate strategic plan must include organizational members on all levels, fire departments must ensure that all levels and demographics are represented in the plan deliberation. A plan that is created by the leadership team alone is doomed to fail.

An organization must commit to implementation and strategic management for success to be found. Without true strategic management, the time invested in the planning effort creates a dust collector to rest amongst the many training manuals in your stations. For strategic planning to work, implementation must always be a part of the organization’s focus. It is not about being a model developed in the private sector, it is about a model that holds an agency accountable for change. Implementation is not easy and there is no magic elixir that makes it reality. However, you owe it to your department to continue toward implementation. Consider this…there is a reason why the accreditation model not only requires a strategic plan but a management plan for implementation. Core competency 3A.1 requires that an agency have a strategic plan. Additionally, core competency 3C.1 requires that some sort of management process exist to track progress toward achieving the set goals in the plan. Execution is everything. And finally, core competency 3D.1 requires that an organization visit its goals and objectives annually and revise if needed. This ensures that your agency has created a living document; and in reality, it should be visited more than just annually if an organization is committed to change and continuous improvement.

So, understanding the applicability proves that this model still works within the public sector. But what about best practices and any emerging trends? The applicability covers many of the best practices of strategic planning. However, one must also consider the facilitation and the sifting required to get a more global view of the gaps that exist. There is no requirement that facilitation come from the outside. It is quite possible that someone within your organization has the knowledge, skills, and abilities to facilitate effectively. The downside to this is the facilitator does not get to participate and bias can sometimes exist, turning the planning process away from the true issues facing the agency. Outside facilitation takes away the bias but does not contribute to the overall knowledge of the department stakeholders. It is a decision left to consider internally.

The other key points of applicability truly link to best practices. A fire service agency must continue to sift through the causal issues to get to the true broad gaps that challenge the organizations growth and forward momentum. Without this, it is just spinning its wheels in tactical minutiae. The community feedback gathered can help break through this, understanding that the feedback internally also carries a great deal of weight. There really must be a clear balance.

As for emerging trends, research indicates that departments must continue to monitor the environmental trends in which the plan exists, and the organization operates. While a typical strategic plan is still relevant in a three to five-year period, organizations must continue to monitor the industry and even greater, the community and adapt accordingly. Bearing in mind environmental trends and changes, the agency must continue to strive for implementation, even if re-calculation is required.

Consider this…what is your department doing to move things forward in a strategic manner? Sitting back will not help you in the accreditation model but worse, will ensure you do not meet the demands of your community. There is no perfect solution to strategic planning and there are many references that can provide the mechanics of the process. However, doing nothing toward implementation can ensure greater strategic issues. It is important to understand that a business model can actually apply to the public sector. While we are beholden to our community versus private shareholders, we still have a customer base. Ensuring we listen to them and determine the causal aspects of service and performance gaps will only help us sustain and grow more in the future.

Brian Dean retired as an Assistant Chief after 28 years of service with the Winter Park Fire-Rescue Department. Chief Dean has extensive background in fire service operations, support, and accreditation. Brian continues to work with the fire service in many areas of accreditation by serving as a Mentor, Peer Assessor and Team Leader, as well as a Technical Advisor, Strategic Planning Manager, and instructor for the CPSE.

In 2015, Brian was awarded the Ray Picard Award by the CFAI. Chief Dean’s educational background includes a Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration from the University of Central Florida; and a Master’s of Science in Leadership from Grand Canyon University. Additionally, Chief Dean graduated from the Executive Fire Officer Program (EFOP) from the National Fire Academy and continues being professionally credentialed as a Chief Fire Officer (CFO) from the Commission on Professional Credentialing (CPC).