During my travels to consortiums across the country, I often hear the refrain that data (hear date-ahhh) is the biggest obstacle for departments working towards and maintaining accreditation. I have jokingly characterized data as another four-letter word used to express frustration. This attitude towards data is caused not by an apathy towards the usefulness of it but rather by the challenge of acquiring, compiling, and analyzing it.

This article outlines some concepts that will (hopefully) assist in shifting data from being tolerated to being embraced and the steps CPSE is taking to elevate the role of analysis in the fire and emergency service.

Not all data are created equal

A fire department’s relationship with data and performance should be seen as a continuum. Statements regarding a department’s need to have “good data” and “good performance” are numerous. However, these statements do not mean the same thing.

The beginning of the quality performance continuum is for a department to have “good data.” Good data is defined as data that are based on factual incidents, reported accurately, and can be accessed and manipulated easily. It can take a department a long time to work on their data but it’s important that they do that before trying to improve performance. Without good data there is no assurance that improvement efforts will actually work.

Once a department has improved their data quality, they can begin working on having “good performance.” Good performance is the end of the quality improvement continuum. For example, improving fire station layouts to reduce turnout time, working with the communications center to streamline call processing, conducting targeted staff training, investing in community risk reduction efforts, and deploying additional/alternate resources within a jurisdiction are all ways to improve performance.

A knee jerk reaction to observing a given performance metric for a department may be to say that “the metric is wrong.” However, in determining the root cause, it is important to distinguish whether the data used in the calculations are wrong or the performance itself is poor. Working towards good data is paramount to achieving good performance.

Shifting the conversation from data to evidence

Beyond just raw numbers, qualitative data can also inform decisions. You may be familiar with the differentiation between inputs, outputs, and outcomes. The below categorization of data goes further by providing four additional ways to consider uses for data:

- Descriptive data defines what happened

- Diagnostic data explains why it happened

- Predictive data permits the user to know what will happen next

- Prescriptive data directs the user in what they should do about it

Efforts to describe, diagnose, predict, or prescribe using data are most successful when infused with expertise. Evidence, rather than data, tells a story using facts and figures while also drawing on the personal experience of the teller and speaking to the motivations of the listener.

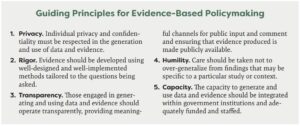

The need to support public policy decisions is evident at the local, state, and federal levels of government. At the local level, what type of EMS response a fire department provides a community is a prime example of evidence-based policymaking. A 2017 report, The Promise of Evidence-Based Policymaking developed by a federal commission sought to reinforce the benefits of such policy making and provides guidance on how best to executive it. The report posited five guiding principles for evidence-based policymaking: privacy, rigor, transparency, humility, and capacity. These five principles are equally useful for local government as they are for federal government.

The need to support public policy decisions is evident at the local, state, and federal levels of government. At the local level, what type of EMS response a fire department provides a community is a prime example of evidence-based policymaking. A 2017 report, The Promise of Evidence-Based Policymaking developed by a federal commission sought to reinforce the benefits of such policy making and provides guidance on how best to executive it. The report posited five guiding principles for evidence-based policymaking: privacy, rigor, transparency, humility, and capacity. These five principles are equally useful for local government as they are for federal government.

Convening the analysts of today

Wanting to hear from those working with data, conducting analysis, and influencing public policy at the local level, CPSE and NFPA co-hosted a one-day Analyst Incubator at the 2018 CPSE Excellence Conference. Twenty analysts and those who supervise analysts from departments across North America met and created a roadmap to grow the count, role, and profile of fire analysts.

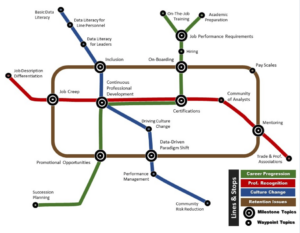

During the incubator, one of the key realizations was that there isn’t a unified linear path that all analysts and fire departments follow. The participants shared their diverse range of skillsets, backgrounds, and career trajectories during the session. Recognizing this diversity, we developed an interactive subway map to illustrate career progression, professional recognition, culture change, and retention issues for fire analysts. As with any subway map, there are spots where two or more lines converge. In our subway map, data-driven paradigm shift, continuous professional development, and certifications, were the converging themes.

During the incubator, one of the key realizations was that there isn’t a unified linear path that all analysts and fire departments follow. The participants shared their diverse range of skillsets, backgrounds, and career trajectories during the session. Recognizing this diversity, we developed an interactive subway map to illustrate career progression, professional recognition, culture change, and retention issues for fire analysts. As with any subway map, there are spots where two or more lines converge. In our subway map, data-driven paradigm shift, continuous professional development, and certifications, were the converging themes.

The interactive subway map and a webinar that I co-presented with Dr. Matt Hinds-Aldrich, NPFA’s Program Manager, Data and Analytics, can be found on the Fire Analyst page on the CPSE website.

Envisioning the analysts of the future

Having understood the challenges faced by today’s fire department analysts, CPSE submitted a request to NFPA to develop a fire analyst professional qualification (Pro-Qual) standard. Given the complexity of gathering and analyzing data for accreditation and the growing sophistication of technology systems available to fire departments, CPSE believes a Pro-Qual standard for fire analysts is an important next step in the progression of fire departments. NFPA is collecting comments through March 15, 2019 to determine if the standard is in fact needed. You can read the full notice on the NFPA website.

A recent Harvard Business Review article highlighting the 2016 McKinsey Global Institute publication The Age of Analytics: Competing in a Data-Driven World, introduced the concept of an analytics translator that will “play a critical role in bridging the technical expertise of data engineers with operational expertise” and will “help ensure that the deep insights generated through sophisticated analytics translate into the impact at scale in an organization.” By 2026, McKinsey estimates the demand for analytics translators in the United States alone may reach two to four million.

Law enforcement has long valued the role of analysis in supporting their field work evidenced by not only the ubiquity of large monitors in TV shows about police departments but the real world existence of approximately 3,600 crime analysts. Imagine a world where TV shows featuring a fire department showed a fire department employee sitting behind a large monitor supporting the work of the field personnel.

Whether uniformed or civilian, the number of analysts working for fire departments has grown significantly in recent years. These individuals may have titles ranging from Battalion Chief of Planning & Assessment, Fire Statistical Analyst, Business Improvement Manager, to Assistant Chief of Administration. On almost a weekly basis, there is a new job posting for “(fill in the blank) analyst” to work in a fire department. The details of the postings are inconsistent, at best, and often do not garner candidates with the right knowledge, skills, and abilities to meet the needs of the fire department. CPSE submitted the request to NFPA, to address just this inconsistency.

Where do we go from here?

Conversations about “big-data,” “open-data,” and “data-based decision making” aren’t going anywhere and seem to be intensifying. Couple this with demands by municipal administration that budget requests be based on performance and demands by the public for greater transparency, fire departments need to transition how they tell their story. Having qualified and engaged personnel to guide this analysis is critical. Even more critical…leaders who not only tolerate but embrace the value of data and its varied uses.